Reading time: 8 minutes

ETHICS EXPLAINED – PART 3

THINGS TO KNOW In the course of human history, numerous religions have developed in the most diverse forms. They all share a belief in something supernatural. But what is it exactly, this transcendent being, and can its existence be proven?

Around 95% of people on earth are believers. But what does “being a believer” actually mean? Belief in a god? Well, that’s called monotheism. Belief in many gods? Polytheism. There are at least 9,900 independent religions worldwide. Are they all equally true? The five world religions are best known: Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism. This article will deal with the basic questions of the philosophy of religion.

Note: Philosophy of religion is not able to prove the existence or non-existence of a god (or gods). With this article I do not want to attack anyone or judge religions of any kind. I will merely take a closer look at some food for thought from the philosophy of religion.

Concept of religion

Before I get to the actual topic, I would first like to discuss the general concept of religion. A “religion” refers to the idea of something transcendent. It is a worldview that speaks about the relationship between the human and the divine, thereby describing the path to happiness and setting standards of action. Roughly speaking religion has four functions:

- the ideological function: Religion interprets the world and its origins and creates a certain image of man.

- the psychological function: It offers support, happiness, hope or a meaning to life.

- the instructional function: It sets value standards or describes cultic norms (such as a daily prayer).

- the social function: It conveys values for (the religious) society.

Taking Islam as an example, this means: Allah as the only God is considered the creator and judge with his messenger Mohammed (ideological function). They can turn to him as a protector in difficult times, so Islam gives its followers support in a certain way (psychological function). Cultic norms are set, such as the five times daily prayer (instructional function) or the almsgiving of wealthy Muslims (social function).

How do I find God? – Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274) was one of the most important Catholic philosophers in history. He pointed out his “Five ways to god” (which I have summarised below) and thus also laid an important foundation stone for his later proofs of God.

- Things move: Nothing moves by itself, there must be a trigger (first mover) that is not moved by anything else – and that is God.

- Effects are brought about by causes: Nothing is the cause of itself. This must lie outside of itself and temporally before. But if every effect needs a cause from outside, a chain of causes and effects without a beginning is created. Finally, there must have been a first cause that caused itself. And this is supposed to represent God.

- Possible presupposes necessary existence: Everything (including thoughts) does exist, but it is only possible (it does not necessarily have to exist) and first needs a “force” to become real. Thus, virtually nothing exists. So there must be a necessary existence that exists in all circumstances and ensures that everything else also becomes true.

- Things possess a varying degree of perfection: Everything can be subordinated/superordinated in a system, whether it is beautiful or ugly, true or false; except for one thing: that which stands at the top and is infinitely perfect must be something transcendent, i.e. a “god”.

- All being has an inner purpose: Nothing exists by chance, otherwise there would not be this interplay between all that exists – someone must direct life on earth.

Four well-known proofs of God

So-called “proofs of God” come in many varieties. The proofs I am presenting here are not intended to prove the existence of God, as one would initially assume. They are more philosophical than theological questions, so the aim is not to provide an unambiguous answer. It is rather a question of the origin and justification of the human idea of a divine being and an attempt to support the belief with rational, valid arguments and to make it comprehensible by applying methods of logic.

- The Ontological Proof (Anselm of Canterbury, died 1109) starts from the definition of God: God exists in thought and is that about which nothing greater can be thought. Since reality always has a greater perfection than thought, God must be real. Especially since the most perfect/highest lies outside of human imagination (thus must be transcendent = proof of stages) …

- The Teleological Proof (Greek “telos” = goal) of Thomas Aquinas builds on his fifth way to God: All things are purposely arranged with a superordinate goal; a goal that no living being (including man) understands. Since everything functions and there are so many types of phenomena, the world must have been created by an intelligent being.

- The Cosmological Proof of God (Thomas Aquinas) states that nothing is the cause of itself. This must be outside of itself and prior in time (cf. Second Way to God).

- Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804) criticised all previous proofs of God. 1. one could not conclude from something ideal to something real, 2. there were also imperfections in nature, especially since it could only be about a controller (demiurge), not a world creator (God) and 3. this law was only observed within our own sense world. He saw only the Moral Proof of God as meaningful: Morality/mindfulness/conscience is given to man – someone must have caused it/wanted it that way.

Why does God make us suffer? – Theodicy question

No matter how convincing one found the proofs of God; another question inevitably kept intruding on man’s consciousness: How can the belief in an all-good and all-powerful, all-knowing God be reconciled with the existence of suffering and evil in the world? – This question, which has been answered differently in different religions, is called the theodicy problem. It was first described by Gottfried Leibniz (1646 – 1716). Leibniz was of the opinion that God had created the best possible world out of many worlds (Leonardo’s world), especially since evils were not bad in principle, but also had their meaning.

In Christianity there were basically two explanatory approaches:

1. God is regarded as the first mover and observer, i.e. he created the world, but man destroyed paradise through sin and is to blame for his own suffering.

2. the purpose of the universe is to drive man to development. If there is no suffering, how are we to recognise the good and develop? (this is called good-evil dualism: good and evil must be in harmony, so there are 7 virtues and 7 deadly sins).

In Judaism, no one is considered completely innocent (“original sin”). And in Islam, even doubting is a sin, since suffering and its endurance are supposed to be closely linked to gratitude for mere existence.

Criticism of religion

Critical statements about religion in general can be summarised under the term criticism of religion. This is not a proof of the non-existence of God, but a rational discussion of statements, functions, origins, institutions, etc. of religion. In the course of history, the following three philosophers in particular have stood out with their critique of religion:

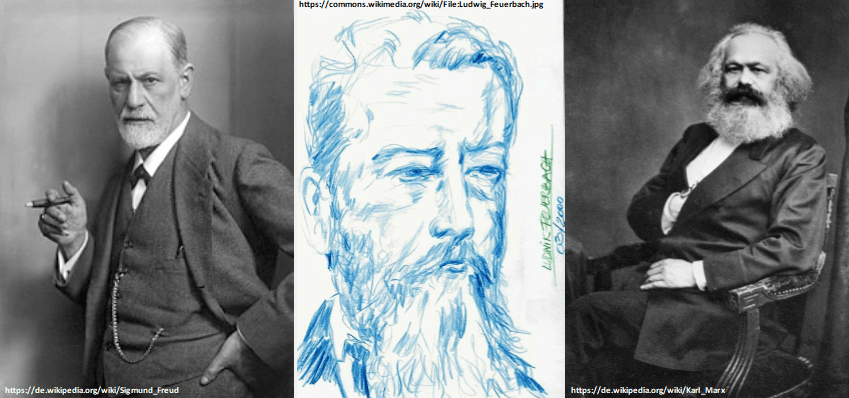

According to Ludwig Feuerbach (1804 – 1872), God is only a “projection of man“. According to him, this points to a “topsy-turvy world”, because in reality it was not God who created man, but man who created the figure of God as a model. In order for man to be the highest being again (and self-alienation to be dissolved), God had to be abolished.

Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939) refers to his instance model in his criticism of religion. He argues that people are not aware that they are driven, helpless and dependent. He sees religion as a reality-distorting illusion and a “father figure created by man” to cope with problems. Religion is not an error, nor is it wrong; it even has a positive effect on some people. But it is not adapted to society and leads to dependence or compulsive behaviour. In these “compulsive neurotics”, the superego with its indispensable moral concepts prevails, while the drives are suppressed.

Karl Marx (1818 – 1883) called religion the “opiate of the people“. It creates a pseudo-happiness in order to endure suffering, but is perceptually distorting (man deceives himself) – so the theory goes. In doing so, it fulfils two functions; the protest function (ideal image of the world = challenging contrast to reality) and the consolation function (consolation over life). It is an instrument of oppression for the poor and self-soothing for the rich. According to Marx, the goal should be to reverse social/political conditions (class struggle …) so that God becomes superfluous.

Religion and science

Today’s critics of religion often refer to the latest findings of science: Why do we need a God if science can explain everything? But faith and science do not necessarily have to contradict each other. Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955) once commented on the relationship between faith and science: “Both should be tolerated and do not contradict each other, more than that: they are mutually dependent, because they ask for absolute knowledge and the meaning and purpose of existence. In the process, religion creates mystery, while science tries to explain it … “

Thus, there are quite a few scientists who openly admit to being religious; for example, by believing in a force that guides nature. For if we are honest, science is unable to prove the existence or non-existence of supernatural beings for any single religion. And so the answer to the question: Is there a God? remains with each individual.

I hope that I have given you something to think about with this – only brief – insight into the philosophy of religion, or that I have provided you with a few ideas with which you can now answer the question in the title of the article for yourself. Unfortunately, due to the length of the article, I could not go into detail about individual religions. If you are interested, you can click here.