Reading time: 13 minutes

File:Germany-00155_-Holocaust_Memorial(30327228915).jpg

THINGS TO KNOW The Holocaust, a genocide of the Jews by the Nazis during the Second World War has shaped German history like hardly any other historical event. But most of us are not aware of the resulting responsibility of the German people.

WITTENBERG, 2018: Pupils of the Luther Melanchthon Gymnasium Wittenberg erect stelae in memory of the victims of the Reichspogromnacht. Nevertheless, many of them do not know the exact background of this tragic event that shaped history. And this despite the fact that on 20/01/2022 the decision of the so – called “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” will be exactly 80 years ago. Determined at the Wannsee Conference, the systematic persecution of Jews by the National Socialists in the Third Reich – what is called Holocaust – now reached its climax.

This fictional interview with the historian Dr Dan Diner is intended to report on the exact events as well as the historical background of the Holocaust and to provide food for thoughts on a very important question: What is the significance of the cruel genocide for us today?

Topic of the Holocaust

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

wiki/File:Roemerberggespraeche-2013-10-dan-diner-ffm-363.jpg

Dr Diner, you are not only a professor at the History Department of the University of Leipzig and former director of the Simon Dubnow Institute for Jewish History and Culture. You yourself have a personal connection to the subject of the Holocaust. To what extent?

Dr Diner: I was born in 1946 as a child of Polish-Lithuanian “displaced persons”. My parents had lost their own families during the Holocaust and it was difficult for them to find their way in post-war Germany. But they managed to emigrate with me to Israel for a few years.

How did your childhood affect your later life?

My roots and my connection to the Middle East definitely sparked my historical curiosity. I eventually turned the perspective of a detached observer I had as a child into my profession. There were so many unanswered questions that my parents had not been able to answer.

You dealt with the Holocaust intensively. Around 6 million people lost their lives in this systematic genocide. What is special about this event?

There have been several mass murders in the form of massacres in history. But in the case of the Holocaust, something unique happened: the systematic extermination of people – just for the sake of extermination. Presumably, about two thirds of the victims died in one of the numerous concentration camps of the Nazi regime. The most famous of these “labour and extermination camps” include Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:

Bundesarchiv_Bild_152-26-20,_KZ_Dachau,_H%C3%

A4ftlinge_bei_Zwangsarbeit.jpg

Numerous sources attest to the cruelty of this act, to which the term ‘industrialised mass murder’ is often ascribed. Where does this term come from?

From 1942 onwards, the murders were not only systematic, but even followed industrial methods. During the Holocaust chemical weapons were also used in the assembly-line killings to eliminate as many people as possible at the same time. Examples of this are the gas vans, in which people were locked up and exposed to poisonous engine exhaust (carbon monoxide).

Over the years, these had developed into ever larger gas chambers, where many victims were murdered with the prussic acid insecticide Zyklon B (e.g. in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Belzec or Mauthausen). Those who were not directly killed there suffered from systematic malnutrition, forced labour, torture or disease. Thus, quite a few people served as “human material” for cruel medical experiments.

The climax of the persecution of the Jews

The exact number of victims of the Holocaust is unclear. But it is certain that the majority of them were Jews. Why?

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_102-14468,_Berlin,_NS-Boykott_gegen_j%C3%BCdische_Gesch%C3%A4fte.jpg

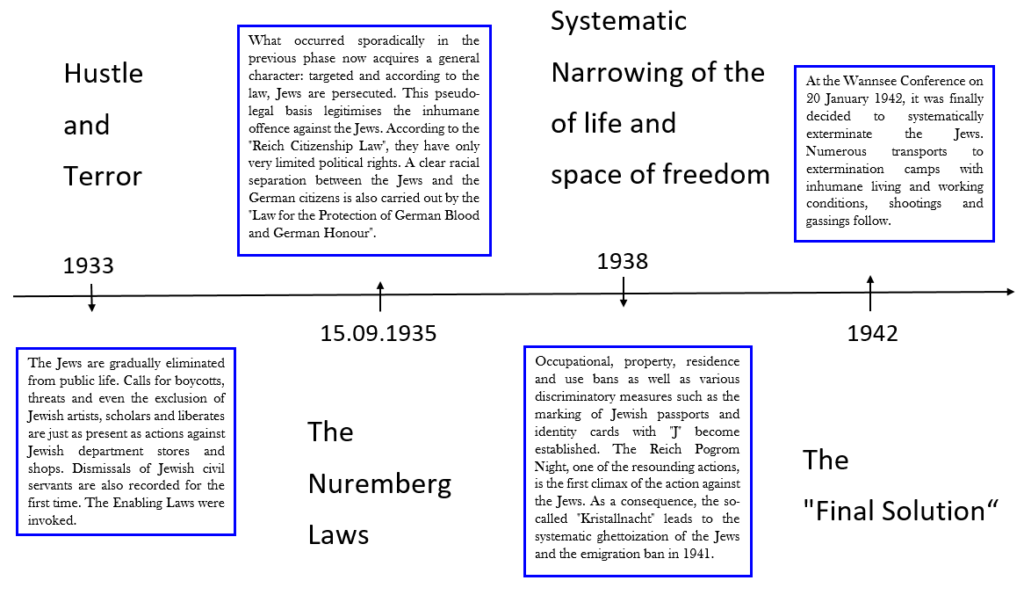

The historical development towards the Holocaust was based on the “racial doctrine” developed by the Nazis. According to this, the “Aryan” (German) race was destined to rule, while the Jews were considered “inferior”. The racial doctrine had always been a central component of the ideology of the National Socialists. During their rule in Germany 1933 – 1945 it had been particularly evident in the systematic exclusion and persecution of Jews, a self-radicalising process that was not necessarily planned to completion.

After the rights of the Jews had been increasingly restricted with the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, the Reich-Pogrom-Night, also called “Reichskristallnacht”, followed on 9/10th November 1938. In this act of terror, SA and NSDAP members set fire to synagogues, destroyed more than 7,000 Jewish retailers’ shops and vandalised homes. As a result of the riots, approximately 1,300 people lost their lives.

The actual Holocaust did not take place until the Second World War, after the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” had been decided at the Wannsee Conference on 20th January 1942. This no longer included the mere resettlement or deportation of Jews to ghettos, but their targeted extermination.

This biologistic understanding of the world and the striving for “racial unity” are seen today by many historians as important ideological preconditions for the Holocaust. What other preconditions had to prevail?

Well, in terms of implementation, we have already referred to the simple technical possibilities. But the genocide also required the strong bureaucratic structures of the totalitarian state. The moral distance of those in command was only maintained by the strong division of labour, a complex system of decision-making structures. And last but not least, the war had played into the cards of the Holocaust criminals. This unreal situation is today described by many of my colleagues as a ” opportunity”.

“Once-in-a-lifetime opportunity”. Why?

I think the historian Götz Aly put it well when he said that the war had promoted “an atmosphere of the non-public”, it “atomised people, destroyed their remaining ties to religious and juridical traditions”. This rupture of values – also in the population – had of course begun before, but had come to its climax in the Second World War.

Fundamental change in values

You speak of a break with traditions. Where exactly do you apply this term?

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:

Bundesarchiv_Bild_101I-134-0766-20,_Polen,_

Ghetto_Warschau,_Juden_auf_LKW.jpg

Well, let’s take bourgeois society as an example. Before the time of National Socialism, there were bourgeois legal norms in the established welfare state system. Values such as freedom of expression, the free market economy and the free practice of art and science had emerged. But equality rights also prevailed, for women as well as for formerly discriminated minorities.

What became of these values under National Socialism?

Now the bourgeois hierarchy of property and education was replaced by a totalitarian state apparatus that determined all areas of the population’s lives. Legal security gave way to state arbitrariness. Strict and harshly enforced censorship made the expression of opinion very dangerous. The state also controlled the economy and disseminated its own “sciences” via an elaborate propaganda system, although these were based more on ideology than science.

And part of the Nazi ideology was the racial doctrine.

Right. So anti-Semitism intensified. But other social groups, in principle all those who were considered “alien to the community”, also lost their rights and became victims of the Holocaust later. These included minorities such as Roma and Sinti as well as homosexuals, criminals or “asocials” (people without a fixed abode). Many were labelled “Reich citizens 2nd class” at an early stage and subjected to forced sterilisation and their own “gypsy camps”. The list of Nazi crimes at this point is long.

Furthermore, there were the physically or mentally handicapped, whose later cruel treatment is also attributed the term “euthanasia policy”. It is assumed that in addition to Jews, 0.5 million Sinti and Roma, up to 3 million Polish and Russian civilians and over 3 million Russian prisoners of war as well as about 100,000 disabled/sick people perished at the hands of the National Socialists. But I digress.

The frightening thing about this development was that a large part of the population perceived the division into the different groups of people as almost normal over time. So there was a progressive normalisation of actually radical exclusion.

A new community

What do you think made the population participate in this exclusion? After all, according to their former values, they could certainly be described as enlightened people.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

File:Bundesarchiv_B_145_Bild-P046284,Berlin,_Reichspr%C3%

A4sidentenwahl,_Werbung%22Stahlhelm%22.jpg

An important aspect was certainly the idea of the “Volksgemeinschaft” (people’s community) spread by the propaganda. This promise of a classless society, political unity and national resurgence was able to mobilise large sections of the German population. The fact that this “community” also had an exclusionary character towards Jews and minorities was perhaps not so strongly realised by many at the beginning.

But what exactly was this attraction?

Well, the people’s community created a sense of social equality and individual opportunities for advancement – even if this was not entirely true. Women, for example, were now supposed to serve “the propagation and preservation of the race”; they were not entitled to leadership positions in state and society. Associations such as the “Bund deutscher Mädel” (Association of German Girls) or the “NS-Frauenschaft” (National Socialist Women’s Association) skilfully concealed the actual National Socialist intentions.

Feelings of loyalty to National Socialism were also largely aroused by the economic upswing, the reduction of unemployment and growing consumer opportunities. It should not be forgotten that these processes of inclusion and exclusion also exerted an emotional binding force. Only very few “pure Germans” wanted to be excluded from the “community” and miss out on the “upgrading of the people’s comrades”. Morality and sociality thus definitely prevailed among “community members”.

Propaganda also seems to play its part. You have already spoken of an “elaborate propaganda system”.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-K0930-502,_Wahlplakat

_der_NSDAP_zur_Reichstagswahl.jpg

Propaganda was considered at the time to be the most important legal means of moving the masses and spreading Nazi ideology. With the most modern media, buildings, sightseeing flights, etc., the government could not only create a sense of belonging. It was also possible to use language to deliberately obfuscate or blunt. For example, “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” probably sounds much more positive than “extermination of the Jews”. Especially Hitler was particularly famous as a propaganda figure for his rhetorical skills of persuasion.

Adolf Hitler is also often referred to as a “charismatic leader” in this context. What do you say to this?

This view is still a controversy (disputed) among historians today. But whether he actually had magical abilities or not: one thing is certain, there was a certain “willingness to believe” among the population in the great leader and a general acceptance of the absolute authority of the leader. In this way, the previously prevailing democratic values of the Weimar Republic were virtually abandoned.

Certainly, the Weimar Republic also had weaknesses, which the National Socialists deliberately exploited. But did people really just accept the dictatorship, the racial doctrine, the exclusion? Was there no resistance?

Of course there was resistance. But the Nazi regime had already taken care to eliminate all political opposition and opponents before coming to power. Anyone who thought differently was strictly monitored, persecuted or even shot. As a result, many people simply withdrew or tried to block out aspects such as exclusion from their lives.

Active resistance thus only gained real significance during the Second World War, when the situation came to a head. Circles of social democrats, trade unions, churches, students, etc. formed. Even individual high-ranking officers, for example in the Wehrmacht, joined the resistance. However, their political calls, putsches and assassination attempts remained virtually ineffective until 1945.

We knew nothing

A large part of the population claimed at the time to have known nothing about all the terrible crimes during the Holocaust. Is that a credible statement?

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:

Bundesarchiv_Bild_101I-680-8285A-08,_Budapest,_Festnahme_von_Juden.jpg

Although the technical information channels did not exist back then as they do today, it can nevertheless be said that a part of the population did know or at least had an inkling. So of course it was noticeable when neighbours or classmates suddenly disappeared from life. City administrators deleted their names from the address books. Engine drivers drove the deportation trains to the concentration camps.

Dock workers helped load numerous Jewish possessions that were sold cheaply. Wehrmacht soldiers told of the atrocities within the war effort against the East. Workers in the immediate vicinity of the concentration camps could not have been unaware either. Presumably, then, from about 1942 onwards, a general knowledge of the camps and general extermination of Jews had spread through rumours.

And yet the Germans stick to their version of having known nothing.

This plays into the question of individual responsibility for this event. If one says that one knew about it, the question arises at the same time why one did nothing about the Holocaust. This in turn leads to the debate about the individual’s scope for action … Ultimately, we know human characteristics quite well – the historian Peter Longerich has highlighted this – there is also a difference between “being able to know” and “wanting to know”. Why should I make life difficult for myself with thoughts about such cruel rumours when I myself did not have much to do with them?

Breach of civilisation

You deal very intensively with the current significance of this very question. In your work “Gegenläufige Ereignisse. Über Geltung und Wirkung des Holocaust” (Opposing Events. On the validity and impact of the Holocaust) you primarily coin the term “breach of civilisation”. What does this expression mean?

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-H26996,_KZ_Dachau,_Verbrennungsofen.jpg

The extermination of almost 6 million Jews violated fundamental moral and rational “norms of human coexistence”, first and foremost humanity. This fact is undeniable. But it was not only the brutality and violence that constituted the breach of civilisation. Rather, a hitherto cherished ontological security broke down. I want to say that this act apart from conflict, antagonism or political enmity lay outside what was thought possible before the Holocaust.

That the National Socialists even acted against the interest of their own self-preservation was underestimated not only by the Jews. After all, here was a rationally planned mass murder carried out without compassion – and by a highly civilised people. It can be assumed that about 250,000 Germans and Austrians were directly or indirectly involved as “perpetrators”.

Many historians approach the reappraisal of the Holocaust in the familiar manner. You have criticised this. Why?

One cannot generalise the Holocaust and “historicise” it in the original sense, while at the same time highlighting it as THE story of the Germans. Auschwitz as a symbol of Nazi crimes stands for industrialised mass murder and extermination for the sake of extermination; processes that can hardly be interpreted objectively, all-encompassing, with our thinking today.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-R69919,_KZ_Auschwitz,_Brillen.jpg

And yet Auschwitz is still the starting point for current debates about the National Socialist legacy of the Germans.

Auschwitz has so far been regarded as unprecedented, incomparable, unique. I like to use the term “singularity” in this context. But the Holocaust is only singular so far, and that is what I want to state here: it can happen again.

You thus place the term in a universal dimension.

Yes, we must realise that today’s society can also provide the preconditions for the realisation of events of this magnitude that destroy human beings. Today, as then, the foundations of social action are based on the assumption of a certain rationality of man. But what is this reasonableness if people were destroyed for the sake of destruction back then?

Responsibility

Are you saying that the Federal Republic of Germany also sets the conditions for a repetition of the Holocaust?

Well, I wouldn’t put it that way. But it shows that contingent developments can make attitudes possible that one never thought possible before. Anti-Semitism is not a highly publicised today. Even anti-Semitism at the beginning of the 20th century in Germany was nowhere near as aggressive as it was at the end of the 1930s, but it was intensified over time by wounded national pride brought on by the lost First World War.

In addition, there were economic uncertainties such as the inflation of 1923, the world economic crisis of 1929, the subsequent mass unemployment and, last but not least, the loss of social stability and the fear of the middle class against the political left. All these events, which to a large extent took place during Germany’s first democracy, only made the population receptive to the ideas of the National Socialists. This brings us back to my civilisation-breaking thesis, which links the Holocaust to an execution by a – German – “cultural nation”.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

wiki/File:Holocaust_monument_Berlijn.jpg

That gives food for thought, I would say. Any final words on your part?

The Holocaust is an event of relevance to human history. Germans must be aware of the “legacy” left behind by the National Socialists. The debate about the meaning of the Holocaust will continue. And it concerns each and every one of us.

Thank you very much, Professor Diner. At this point, I would like to end the conversation with a quote from one of your earlier interviews: “Coming to terms with the Holocaust, dealing with it, has also become, if you will, part of a civilisation project of Germany”.

Accordingly, it is not just a topic for those interested in history, but shows a high importance in the sense of civilisation, both in the individual and in the overall national sphere. Thus, the undertaking of the Wittenberg students 2018 was by no means wasted, just because not everyone could identify with the motives behind it. It was a small step of reappraisal. A small step in a large civilisation project.

For those interested, here is more information on the Holocaust and judeophobia or the SKW Piesteritz.